-

Share on

Science Europe Symposium 2017

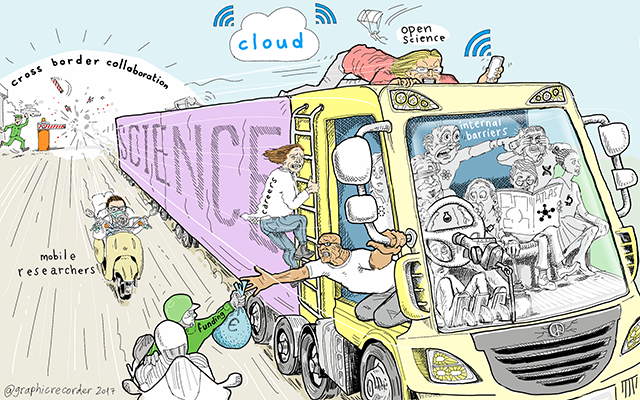

Science Without Borders

For the second Science Europe Symposium, organised together with the Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) of Science Europe, its members had asked themselves what a ‘science without borders’ would look like. What do they, as active scientists, consider to be the most important enablers for and barriers to a truly borderless science?

On 29 November, Science Europe members met with scientists, policy makers, and representatives of society at the 2017 Symposium to discuss their ideas. SAC presented six short pitches on topics that they considered to be most relevant for a ‘science without borders’:

- Open Science

- Researcher Mobility

- Cross-border Collaboration

- Scientific Careers

- Funding

- ‘Inner Borders’

The ‘Inner Borders’ in Science

Although all six topics were identified as important, the so-called ‘inner borders’ in science were chosen to be discussed more in depth. These borders were defined as those between disciplines and sectors when it comes to collaborating on research, but also as those between scientists and citizens in engaging and involving the latter in research efforts. A number of barriers were brought to the table, such as difficulties in evaluating multidisciplinary research, limited funding opportunities, and a too narrow view of innovation.

Science Europe Member Organisations

High-level representatives of Science Europe Member Organisations gave their views on the importance of preventing brain drain, new approaches to evaluation and international peer review, and on moving forward with Open Science. They acknowledged the need to set appropriate incentives and rewards, especially for early-career researchers in a scientific system that is rapidly changing.

European Institutions

Clare Moody (European Parliament), Maive Rute (Joint Research Centre, European Commission) and Ana Arana Antelo (DG Research and Innovation, European Commission) spoke in the session dedicated to society. In discussions with the SAC and the audience, they argued that engaging all of society to work together is a challenge that must be met in order to realise a ‘Science Without Borders’.

The outcomes of the discussions and ideas put forward at the Symposium will be used as input for the work of Science Europe in the coming years. Professor Pearl Dykstra of the Scientific Advice Mechanism, a high-level group of scientific advisors to the European Commission, gave an evening lecture during the reception following the Symposium. She emphasised the importance of having policy be informed by advice from scientists.